Russel Barsh spent a terrible year in high school casting and throwing pots in an industrial ceramics class with an instructor that displayed a pre-ceramic mentality. As an antidote, he began collecting old porcelain and pottery as a university student in Boston. “I never lost the tactile senses of slimy slip, soft clay between my fingers, or the textures made by different glazes,” he explains. “High school left me totally in love with ceramics but utterly unable to throw a pot without looking nervously over my shoulder.” While he studied paleontology and evolution at Harvard, he worked in the archaeology laboratory sorting thousands of freshly excavated Mayan potsherds, and when he relocated to Seattle to teach at the University of Washington, Russel soon found himself on the Seattle Arts Commission, where he spent “idle hours and some spare dollars” visiting local studios, like the kiln shared by Patty Warashina and Robert Sperry in Laurelhurst, and famously being the only male member of the Seattle Antique Ceramics Circle associated with the Seattle Art Museum. He discovered his first pieces of Doulton Lambeth wares gathering dust in Midwestern antique malls while attending academic conferences in the 1980s. “I checked out the artist signature, read up on Lambeth, and I was hooked” he says. “It is a remarkable thing to feel the knife cuts, beads and fingerprints in a handsome pot that was sitting on Lizzie Fisher’s bench nearly a century and a half ago. They are as fresh to me as the works of living ceramic artists that I have known.”

Russel Barsh spent a terrible year in high school casting and throwing pots in an industrial ceramics class with an instructor that displayed a pre-ceramic mentality. As an antidote, he began collecting old porcelain and pottery as a university student in Boston. “I never lost the tactile senses of slimy slip, soft clay between my fingers, or the textures made by different glazes,” he explains. “High school left me totally in love with ceramics but utterly unable to throw a pot without looking nervously over my shoulder.” While he studied paleontology and evolution at Harvard, he worked in the archaeology laboratory sorting thousands of freshly excavated Mayan potsherds, and when he relocated to Seattle to teach at the University of Washington, Russel soon found himself on the Seattle Arts Commission, where he spent “idle hours and some spare dollars” visiting local studios, like the kiln shared by Patty Warashina and Robert Sperry in Laurelhurst, and famously being the only male member of the Seattle Antique Ceramics Circle associated with the Seattle Art Museum. He discovered his first pieces of Doulton Lambeth wares gathering dust in Midwestern antique malls while attending academic conferences in the 1980s. “I checked out the artist signature, read up on Lambeth, and I was hooked” he says. “It is a remarkable thing to feel the knife cuts, beads and fingerprints in a handsome pot that was sitting on Lizzie Fisher’s bench nearly a century and a half ago. They are as fresh to me as the works of living ceramic artists that I have known.”

WOMEN OF THE LAMBETH KILNS 1868-1908

From humble beginnings as an apprentice potter at Fulham in his native London, John Doulton (1793-1873) and his sons John (1819-1862) and Henry (1820-1897) built a commercial empire in the 1850s manufacturing “sanitary ware”: that is, the new-fangled toilets, water filters and drainage pipes that revolutionized home life in Victorian cities. After his brother John died in 1862, Henry assumed general management of the business. At the same time, he diverted some of the resources of the firm’s Lambeth factory to art pottery in partnership with the Lambeth School of Art, in which Henry became a patron and director.

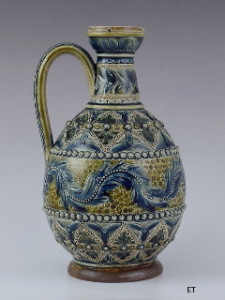

Influenced no doubt by the essays of John Ruskin (1819-1900), who argued that art must be “true to nature” and represent honest handiwork, Henry Doulton recruited young talent from the Lambeth School of Art such as Frank Butler and George Tinworth, to try to recreate the artisanal stoneware jugs and pitchers of medieval Europe using the same clays as Doulton’s drain pipes: clear defiance of the mid-19th century explosion of cheap, fragile, mass-produced color-printed pottery that British kilns were exporting by the shipload. Henry Doulton combined young artistic talent with the technical expertise of Professor Arthur Church, an industrial chemist who worked at Lambeth from 1863 to 1870 on glazes and improving the strength and stability of the ceramic body.

Early experiments were marked Doulton Lambeth, often with a C for Church or the monogram of the modeler. Many that survive today are unfinished. Critical response to the first medievalist wares exhibited in Britain was positive, and Doulton expanded the production capacity of the Lambeth studio, making a crucial decision to recruit women as well as men from the Lambeth School and other British art academies. As the production from Lambeth expanded, its workforce—some 370 potters by 1901 when the factory was granted a Royal Warrant by Edward VII—was increasingly female. Women apprenticed with older women as well as men, and earned the right to their own studios and designs.

From 1872 to 1889, each individual Lambeth piece was stamped with the year, the hand-carved initials or monogram of the senior artist, and the stamped initials of all of the apprentices whose hands had touched it: a rich social and artistic documentary. After 1890, consecutive pattern numbers replaced year marks, but until 1910 most pieces were still individually decorated and signed.

Henry Doulton was a liberal in the best sense of the term in Victorian society. He was convinced that women were capable of equaling men in technical skill and creativity, if they were provided the same resources such as studio space and artistic freedom. At a time when middle-class British society was placing women figuratively on a pedestal, the Lambeth factory was giving women salaries and commercial studios. Ironically, Lambeth was a failure economically; not because it employed so many working-class and educated young women as designers, but because the British public was unwilling to pay for hand- crafted pots when mass-produced ceramics were so much more affordable. Lambeth was in decline by 1910, made a brief revival after the Great War, and died in the Depression.

How did hundreds of young British women influence the Doulton Lambeth wares artistically? This is not an easy question to answer, in light of the vast output of Lambeth within barely three decades of peak activity. It is tempting, when I examine the pieces I have on my shelves, or as photographs in my notes, to suggest that the young women that joined Lambeth in the 1870s brought a sense of detail, of lacy extravagance to decoration, that became hallmarks of Lambeth design until the early 20th century when succeeded by Secessionist, Jugendstil and Glasgow-style simplifications. Pots modeled in the 1860s are very fine medieval knock-offs. Pots of the 1870s are lavishly and meticulously decorated with “jewels” (beads made of clay and glaze), hand-carved leaves, and braided cording (a little like cables in knitting) that are novel and define a distinct Lambeth decorative taste.

Check the signatures on the pots, however, and it is impossible to detect an origin for this decorative style in the work of particular Lambeth women. Men like Frank Butler that were making reasonable facsimiles of solid simple medieval jugs in 1868 are making distinctive, intricately decorative Lambeth pots in 1878, alongside young women like the Barlow sisters, Elizabeth Atkins, Elizabeth Fisher, Eliza Simmance and Florence Roberts. This suggests that the collegial environment at Lambeth produced new ideas shared from the start by male and female colleagues: the ideal promoted by Margaret MacDonald and Charles Rennie MacKintosh at the Glasgow School of Art in 1897-1909.

*******